No matter how you ignore me, I am still your child.

I still look in your face for your words.

When I gain my own I will leave.

Grammar is how people use a language. It is a whole system. These are my notes where I try to puzzle out how the different parts of Hungarian grammar fit together, in the order that I wish I had been introduced to each concept. It is a very personal take on grammar, you may have a different approach and a different organization. The question is, have you ever sat down and tried to organize it for yourself in a way that made sense personally?

The purpose in writing these notes is to clarify things to myself. Imagining myself sharing with others forces me to realize details that I imagine someone asking that I myself do not understand, and so I have to go find out and digest the information and then relay it.

I don't know if my notes will be helpful to anyone else. But I envision one of my nieces, or one of my children, sitting across from the kitchen table from me, and me trying to give an overview of the Hungarian language, in a way that they can be curious and take joy in it. None of them know Hungarian. I am not Hungarian! However I think anyone would find it beautiful to be invited to be part of someone's language.

We will start with one command. It is my favorite Hungarian word.

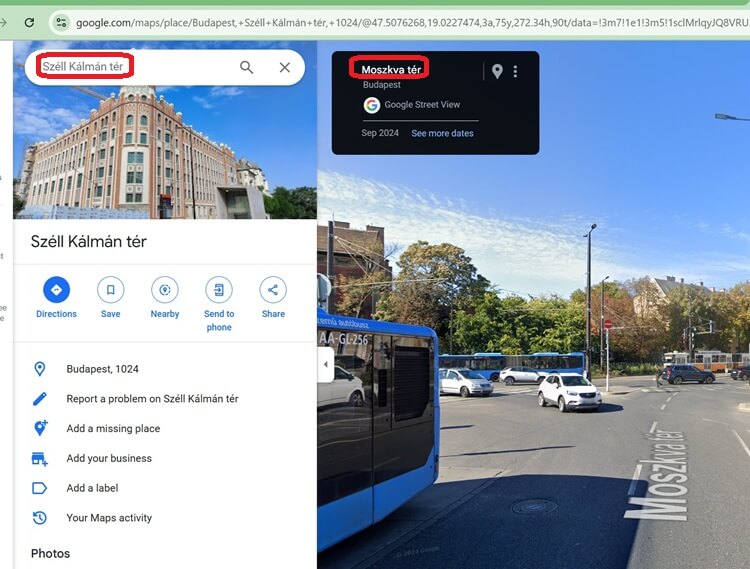

Before I tell you what the word is, I will give you the scene you are in, to hear the word for the first time. The place is "Moszkva Tér."

"Moszkva Tér" is the name of a square on the Buda side of Budapest. It is the crossroads of several trolley and bus lines and it is a metro stop as well. Its name is no longer Moszkva tér ("Moscow Square"). Now it is "Széll Kálmán tér." But when you walk with Google maps, it is very confusing, because using street view, as you walk you will be walking on Széll Kálmán tér, and randomly it will flick to Moszkva tér and then back to Széll Kálmán tér, as if nothing had happened and you didn't just transport back in time just then.

"Moszkva Tér" is the name of a film. It is not necessary to understand Hungarian to enjoy this film. Probably anyone who understands what it means to live would enjoy this film just fine the whole way through. The film is here, if the link still works: https://archive.org/details/moszkva.-ter.-2001.-hungarian.-1080p.-webrip.x-264.-aac-5.1-yts.-mx

People shouldn't think they don't have time to learn a language. If it is interesting, they will be able to learn it, no matter how many hours a day they work.

Anyways, I was watching the film, and a person indicated to another person to come, with the word:

Come!

Since I am writing for multiple readers, I actually should say a different form of the command which was also in the film:

Youse all come! ;)

But I personally like the feeling that someone is speaking only to me when they say "you" to me, even when there might be other people also getting the message. It makes me feel special. I think of all the habits ingrained from English, this will be the hardest for me to shake, that I use singular forms when I address multiple people. Please forgive.

I think "gyere" is the most beautiful Hungarian word.

Gyere!

Hungarian has formal and informal ways of speaking. I had never encountered the word "gyere" before, because "gyere" is the informal form and I had been studying only formal forms.

The formal form of the command "come" is:

If formally telling multiple people to come:

Gyere, gyertek, jöjjön, jöjönnek are forms of the same word (there are many more forms too!). The basic form of the word is:

The basic form is the form in which the word is found in the dictionary. Jön does not mean "to come" (that would be jönni). Jön instead means "he/she/it/(and formal singular 'you') comes." It is called "basic form" because it is considered as having no ending.

This builds on the concept of manners. I frustrated many Hungarians with my carelessness in pronunication at the beginning. It really was just inconsideration on my part, with a touch of arrogance.

For example I didn't think it was important to pronounce the "a" and the "á" sounds correctly. A word had an "a" or an "á" and I would mix them up randomly. Both of the sounds sound to me like the "a" in father -- depending on whether you pronounce the "a" with a British versus an American accent. In English, the meaning of "father" does not change if you say "fohther" versus "faether."

I didn't realize it would render me incomprehensible when I wanted a taxi driver to drive me to Pallag in Debrecen but I pronounced it "Pállag." He just didn't get it. When I finally showed it to him in writing, he said "Pallag!" as if I was stupid. I retorted back as if he were the idiot, "Pállag!" After all, us English speakers have to interpret a thousand variations on our vowels, depending on the region. Was he so dumb he couldn't even guess what I was trying to say? It took a while before I realized I needed to be more attentive.

And for some fun, here is a video on how to pronounce "a":

https://youtu.be/khhojSopRlQ?si=n9Nbicxr_YQ-k2Dp

By watching the above video, you can also see how a lot of the consonants are pronounced (most consonants require a vowel in order to be spoken).

Vowel pronounciation can be learned by learning the Hungarian ABC's. In Hungarian, the word for the vowel is its sound, nothing else. Long and short vowels are separate letters. Long vowels are pronounced for a longer amount of time than short vowels are. Some short-long vowel pairs also have a difference in sound characteristic (in addition to length of time), but not all. Each letter represents only one sound, thus spelling is phonetic. Well, consonant sounds next to each other might merge naturally, but the idea is that each letter has one dependable sound and length.

Here are the Hungarian ABC's:

https://youtu.be/Vld9fYvmZGI?si=HKP9D76-1V5brN8D

By the way, the word for "vowel" in Hungarian is "magánhangzó" which means "sounding by itself."

The word for "consonant" in Hungarian is "mássalhangzó" which means "sounding with something else."

Pronunciation includes sounds of the alphabet, syllable stresses, syllable lengths, rising and falling pitches, cadence, connected speech.

Hungarian does NOT depend on stress-timing like English does. (Of course someone is perfectly welcome to draw out or quicken up words for emphasis. Just it isn't as necessary as it is in English since Hungarians instead use word order to show emphasis.) So vowels are said completely: there are no schwa sounds.

Even though our ability to pronounce will suck at first, it is important for us to understand the theory and to continue training our ear and vocal muscles.

Hungarian spelling is phonetic. As we read silently to ourselves, we want to at least know how the sound should sound in our minds (whether or not our muscles can imitate the sounds, we should at least be able to imagine them correctly).

Here are a few fundamentals about the phonetic spellings of Hungarian words:

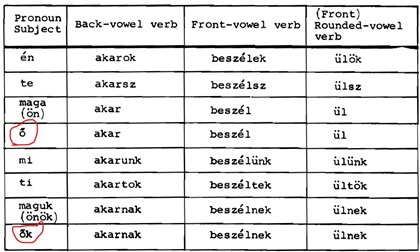

Vowel harmony refers to how a word will only allow certain vowels in it. So when putting a suffix on a word, the suffix will change depending on whether the word has "deep" versus "high" vowels.

Deep vowels sometimes are referred to as back vowels, but Hungarians refer to them as deep ("mély"). Which vowels they are is pretty straightforward - they are the vowels produced relatively low in the throat. They are a, o, u and their long forms.

High vowels sometimes are referred to as front vowels, but Hungarians refer to them as high ("magas"). Which vowels they are is not as straight-forward. The ones produced high in the throat are ö, ü and their long forms. Then there are the ones that are produced in the mid-range, namely e and i and their long forms. While these vowels are usually lumped in with high vowels, there are times that e and i are given honorary status in deep vowel words. So just keep a flexible frame of mind when e, é, i, í show up in deep-vowel words.

Foreign words can have a mixture of deep and high vowels. For such words, the vowel in the last syllable (or second to last syllable if it is a multi-syllable word where the last syllable's vowel is an "i") determines whether the word gets a deep suffix versus a high suffix.

Remember - for foreign words, it is the way the word sounds, not the letters it is written with. So Fort Worth would take a high-vowel suffix, because the "o" in "Worth" is pronounced as a high vowel ("ő").

Compound words take the suffix determined by the last word.

Vowel harmony will show up in all words. There is no escaping it. We will practise it every minute we are practicing anything, whether we want to or not. When learning suffixes, we will be shown which type of suffixes are for deep vowel words and which type of suffixes are for high vowel words, and we will practice with certain words. Learning about the suffix itself will teach us the rules, until it becomes second nature and the right suffix just sounds... right. So there is no point in memorizing any rules at the moment.

The mind loves short-cuts... for example, the short-cut of using our own language's vowels and consonants. Our mind won't tell us when we are doing something wrong, since it is using a system that has succeeded perfectly well up to now.

For this reason, feedback is important. We may feel like we are imitating, but we may not realize that we are using our own language's grooved in sounds. Remember, vowels are an infinite gradient, and the vowels of our language probably exist at slightly different resonance than their "equivalent" Hungarian vowels. Consonants also vary, for example with the amount of air we blow, by the parts of our mouth we hit with our tongue or constrict with our throat or nose, and the hardness we use when we hit those parts. We need feedback! We can't feel insulted when someone indicates we are doing a terrible job at pronouncing something.

It is like learning to drive. Nobody should expect a beginner to figure it all out instantly. If feedback is too harsh (someone exhibiting road rage), we can always try to find someone who is more understanding and patient to provide the feedback. Just most people will not provide feedback. Sometimes only the people with road rage will give us what we need to "wake up."

It takes some discipline. It also takes a while to figure out the things that are possible to do. We can't do what our muscles can't do, no matter how much self-discipline and will-power we have. Our challenge is to figure out what our muscles CAN do, but just aren't doing, and strengthen those things until we can get to the next level. It needs a relatively relaxed attitude, like the rest of Hungarian learning - step by step.To begin exercising vocal muscles, try some songs. It is much easier to imitate sounds in a song than in a speech.

We will be practicing pronunciation as we go along, so we don't need to do specific exercises at the beginning. If certain sounds are problems, then we will need to practice those sounds.

Sometimes the issue lies in being unable to register the significance of the difference between two sounds, like how I was mixing up a and á because the difference seemed unimportant to me. I could hear the difference and I could say the difference, I just wouldn't pay enough attention. In such a case, maybe find audio of words with the two sounds that get mixed up and make flashcards with the audio files, and listen, then repeat the word aloud, and then write it before checking the back of the card. This will force attention. Or just practice writing something someone is dictating - it forces us to ask ourselves "what was that vowel?" as we write what we hear.

Here is an example of training to pay attention to the differences in vowel sounds:

https://youtu.be/jU77EuM6C9E?si=AoE4vxG3ZxaEVpXJ

You can also check out this page: speaking!

Remember, shadowing is really just being a baby and mimicking someone else talking. Start with one word utterances and imitate the word. Continue onto sentences.

That's all we are going to say about pronunciation at the moment.

The rules of Hungarian word order are complex, so most grammar books or courses only discuss the topic at the very end of the course. However, the whole system of the language stems from the fact that word order is...

flexible.

If we start with this as one of the basic concepts upon which we build remaining concepts, the behavior of the language makes much more sense.

Flexible does not mean lawless. There are rules. Flexible means the word order rules allow a huge number of possibilities. Each one of those possibilities emphasizes something slightly different, but they are all valid sentences with basically the same meaning.

In English, "the cat is eating the mouse" and "the mouse is eating the cat" have two very different meanings because of their word order. In Hungarian both word orders can be used to mean the same thing, depending on the suffixes (or lack thereof) on the words:

A macska eszi az egeret.

Az egeret eszi a macksa.

"The cat is eating the mouse," is a statement of observation, versus "the cat is eating the mouse, out of all the things it could be eating," which is a statement of focus. See in the second instance, our attention lingers on the mouse.

In English we would indicate the focus by lengthening the vowel in "mouse." In Hungarian we indicate the focus with word order "the mouse [of all things!] the cat is eating." We mark the poor suffering mouse with a "t," so that no matter the word order we know it is the mouse that is being eaten, not the cat.

In Hungarian, a longer vowel is a different vowel entirely so we can't do what English does in ways of lengthening a vowel to show focus.... See why pronounciation basics are an undercut to all else? By understanding the strictness of pronunciation, we see why word order must change to show focus because we cannot play with vowel lenth.

A clause is a mini sentence, but instead of starting with a capital letter and ending with a period, it lives inside a bigger sentence.

Here is an example of a sentence with clauses in it:

"But I envision one of my nieces, or one of my children, sitting across from the kitchen table from me, and me trying to give an overview of the Hungarian language, in a way that they can be curious and take joy in it."

Notice the awkward part where I say:

"and me trying to give an overview..."

How did that get in there? Well, because "me" was functioning in two roles. One was as a noun receiving the action "I envision me." And the other role was as the noun performing the action "I am trying to give an overview." English "solves" this by arbitrarily slaughtering one of the roles: "I envision me trying to give an overview."

Wow. English got rid of as many noun cases as possible. The few inflected cases that have somehow survived - me, him, her, us, them, whom - we often have no clue how to handle. Do we say "it was him!" or do we say "it was he!"? When someone asks "Who wants ice cream?" do we say "I!" or do we say "me!"?

(... Here is one I came across the other day: "thee and me have a 'feel' for this." But "thee" and "me" are objects, how did they come to being used here as subjects?)

Anyway in English, we choose a form arbitrarily and move on. Even if we did care about the rules (which we don't), the roles would be useless in cases where the word functions as both an object and a subject in the same moment.

Not so in Hungarian. Hungarian evaluates each clause, and treats each noun with its appropriate role. So my awkward little clause would be cleaned up to be something like this:

"But I envision that, whereby one of my nieces or one of my children is sitting across from the kitchen table from me, and I am trying to give an overview of the Hungarian language, in a way that they can be curious and take joy in it."

See how the extra two words solves all the problems of the sentence? Now I am not envisioning nieces, and I am not envisioning me. No. Now I am just envisioning "that." Then the following clauses can have their nouns (one of my nieces" "one of my children" and "I") behave as subjects, rather than objects.

At the very least, learn these three words:

The first two are for survival. The last one because sometimes we just have to be polite.

Ok, before we jump in and translate a bunch more small words from English into Hungarian, let's learn some grammar concepts.

Ommitting a being verb: ("be" "am" "is" "are") and winding up with a sentence with no verb is called "zero copula." It occurs in many languages. In English it is not standard, but it certainly is possible ("you ok?").

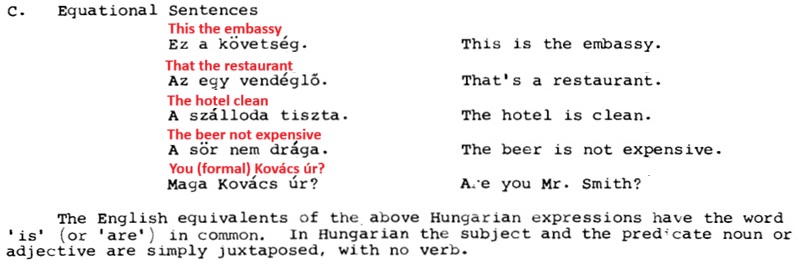

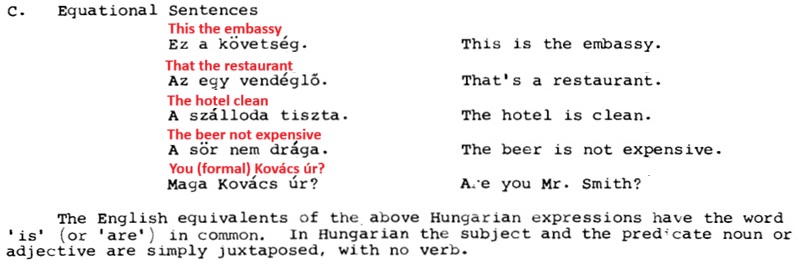

Hungarian does use "is" and "are" extensively, however in certain circumstances it is required to omit them. See this excerpt (my notes in red added) from the Foreign Service Institute Hungarian Basic Course (page 10), where none of the Hungarian sentences show any verb:

The only reason we need to mention this before we go further is so we aren't thrown off when we start to see sentences that omit the word "is" in Hungarian

We will start with the simplicity of the concept, however in later lessons we might be in for some twists and turns.

The English word "a" ("an" before a vowel) is called an "indefinite" article. An indefinite article is the word you use in front of a noun to show that the noun is one of any of its class. "I see a lion."

The English word "the" is called a "definite" article. A definite article is the word you use in front of a noun to show that the noun has been mentioned before or is known specifically. "The lion is beautiful."

Indefiniteness might imply some sort of vagueness, so maybe we won't get in trouble.

Definiteness might imply some sort of ownership or uniquely identify a thing:

"I ate a cake for breakfast." [indefinite article]

"I ate the cake for breakfast." [definite article]

Sometimes the line gets blurry. In English we can sometimes use either "a" or "the" to make a general statement about all members of a class and it will mean the same thing:

"A lion is known as 'king of the beasts.'"

"The lion is known as 'king of the beasts.'"

Some languages do not use articles. The context is enough to show whether the item was mentioned earlier/is known specifically:

"I see lion. Lion is beautiful."

In English, if we don't use an article, it means it is indefinite.

"I see water." [no article, so it's indefinite]

"The water flows westward."

"I see mountains." [no article, so it's indefinite]

"The mountains are beautiful."

"School sucks." [no article, so it's indefinite]

"The school sucks."

"I ate cake for breakfast." [no article, so it's indefinite]

"I ate the cake for breakfast."

There are also definite and indefinite pronouns and adjectives. (Yah they aren't called just "pronouns" and "adjectives" - they are called "demonstrative pronouns" and "demonstrative adjectives" or maybe "determiners" or whatever mouthful somebody wants to feel smart using. I just don't see the point in calling them anything other than pronouns and adjectives.)

"It" is a definite pronoun. It refers to something that was mentioned earlier.

"I see a lion.""Some" is an indefinite adjective. It can also be used as an indefinite pronoun.

"I see some lions." [indefinite adjective]

"I see some too." [indefinite pronoun]

"This" and "that" are definite adjectives. They can also be used as definite pronouns.

"I see that lion." [definite adjective]

"I see that too." [definite pronoun]

"This lion is too close." [definite adjective]

"This is dangerous." [definite pronoun]

To simplify things, whenever I can get away with it, I am going to throw out even the words "article, adjective, pronoun" and just talk about whether a noun is "definite" or "indefinite."

We have to keep straight in our mind when to switch between marking our nouns as definite versus indefinite. We would sound strange if we said "A best thing about a vacation is a plane flight." It would be more natural to say "The best thing about a vacation is the plane flight." But how do we know? Do we think of elaborate rules? If we had to stop and think, it would take a lot of thinking.

In Hungarian, definiteness and indefiniteness requires not only that the descriptor for the noun is correct, but also that the verb associated with that noun is correct.

This gets tricky sometimes, because we aren't used to looking at a verb and thinking about whether it is associated with a noun and if so, whether the noun is definite or indefinite.

Right now we are not going to look at the function of the noun (what is the noun's role in the sentence - is it an "eating cat" or is it a "being eaten mouse"?), because right now we have already discussed quite a few grammatical concepts and we need to keep things as minimal as possible at the beginning. This is just a basic overview. We simply need to become aware of the definiteness of a noun and we need to keep in mind that the verb might change as a result.

Ok, let's learn these small words!

The word for "yes" is "igen."

The word for "no" is "nem." This can also mean "not."

The word for "thank you" is "köszönöm." This word can have other forms, for example, "we thank" is "köszönjük.

The thing we are saying thanks for is marked with (-t). Any time something is marked with a "-t," its definiteness or indefinitess will affect the verb that acts on it.

Example of an indefinite use of the verb: "köszönök" mindent." ("I thank for everything.")

Example of an definite use of the verb: "köszönöm" az egeret." ("I thank for the mouse.")

The person whom we thank (if we mention them) is marked with (-nak/-nek). ["-nak" is used with deep vowel words ("macskának") and "-nek" is used with high vowel words ("egérnek")]

"Köszönöm a macskának az egeret." (I thank the cat for the mouse).

Usually, the thing we are saying thanks for is a definite thing, even when we don't mention it.

"Köszönöm!" actually means "I thank for that specific thing."

The word "köszön" also means "greet." When it is used to mean "greet," it is always indefinite. The person whom we greet is marked with (-nak/-nek). Thus "köszönök a macskának" means "I say hi to the cat."

The word for "is" (as in "he/she/it is") is "van."

The plural ("they are") is "vannak."

Remember, "van" and "vannak" are omitted in certain circumstances.

The word for "the" is "a" or "az." "Az" is used if the word following starts with a vowel, just like the way English uses "an" instead of "a" when the word following starts with a vowel.

The word for "a/an" is "egy"

"Egy" is also used for the word "one," which may or may not be an indefinite pronoun. Usually it is considered indefinite, but if it has a definite adjective, such as "the" or "that" in front of it, it is quite definite ("this is the one," "Oh Great One!")

The word for "but" is "de." It is a nice little onomatopoeia. You are going along nicely explaining something but then you realize that there are subtleties that mess up your logic. So you interrupt yourself mid-stream with "de" and veer off onto a different stream. Or someone else butts in with "de" to cut your flow.

The word for "it" is "ez." Oddly enough, this is also the word for "this." For years I assumed the word in Hungarian for "it" was "ő" (plural ők) because in conjugation tables that's the pronoun listed for 3rd person.

Yah, so anyway, the word for "this," if it is used as a pronoun, is same as the word for "it," namely "ez."

Pronoun: Ez egy macska, nem egy egér." ("This is a cat, not a mouse.")

The word for "this" if it is used as an adjective, is "ez a" (or "ez az" if it precedes a word begining with a vowel)."

Adjective: "Ez a macska nem egy egér." ("This cat is not a mouse.")

Adjective: "Ez az egér nem egy macska." ("This mouse is not a cat.")

The word for "that," if it is used as a pronoun, is same as the word for "the," namely "az."

Pronoun: Az egy macska, nem egy egér." ("That is a cat, not a mouse.")

The word for "that" if it is used as an adjective, is "az a" (or "az az" if it precedes a word begining with a vowel)."

Adjective: "Az a macska nem egy egér." ("That cat is not a mouse.")

Adjective: "Az az egér nem egy macska." ("That mouse is not a cat.")

"Ez" and "az" take on endings just like nouns do.

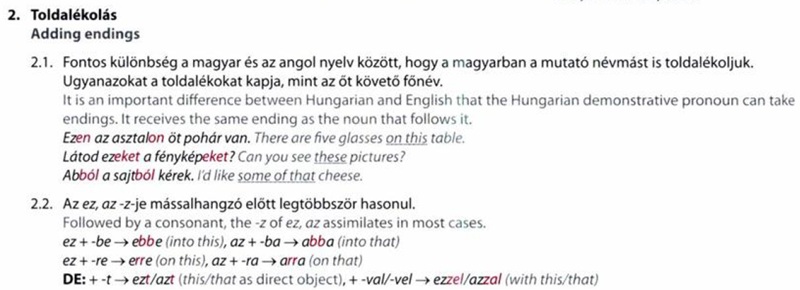

This excerpt from "A Practical Hungarian Grammar" (page 216) explains:

The difference between "this" and "that" is similar to English, where "this" is closer to the speaker than "that."

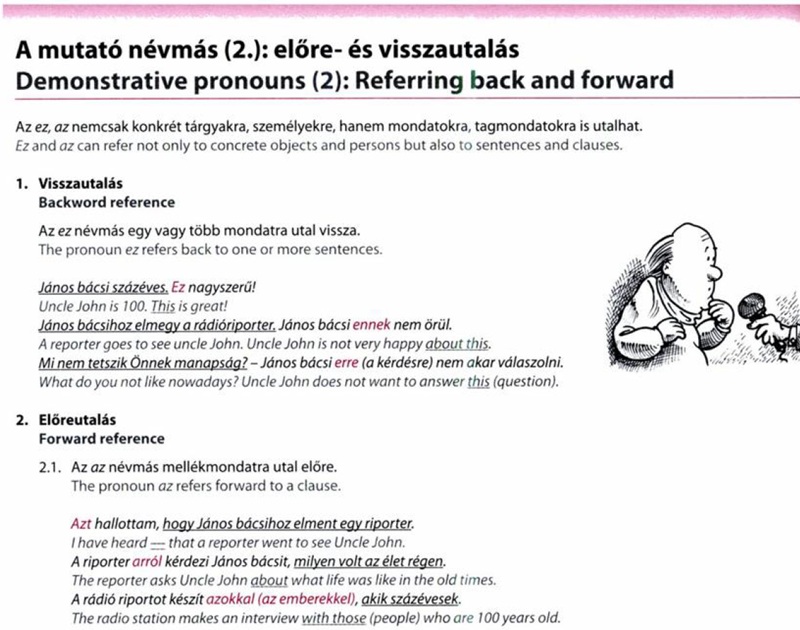

In Hungarian, "this" and "that" also refer to things we have just mentioned versus things we are about to mention.

This excerpt from "A Practical Hungarian Grammar" (page 218) explains:

The word for "what" is "mi." It is a question word. It is an indefinite question word.

Mi az? (What is that?)

If you want to use it as a pronoun you have to add "a-" to the front of it:

ami.

Ez az, ami büdös. (This is what stinks.)

As a pronoun it also is indefinite.

Like all pronouns and nouns, it can take endings.

The word for "when" is "mikor." It is a question word. It is made up of the words mi (what) + kor (time).

We won't discuss whether it is definite or indefinite, since it won't take the -t ending.

Mikor eszik a macska? (When does the cat eat?)

If you want to use it as a pronoun you have to add "a-" to the front of it:

amikor.

Amikor van egy egér. (When there is a mouse.)

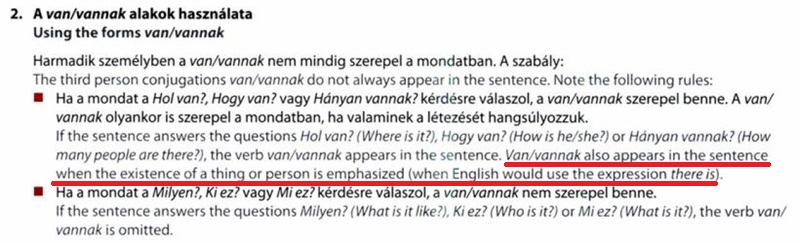

How fun. Here was a time where we did have to use "is" ("van") in Hungarian. Here is the excerpt from "A Practical Hungarian Grammar" (page 44) that shows why:

Ok - back to small words!

The word for "here" is "itt."

The word for "there" is "ott."

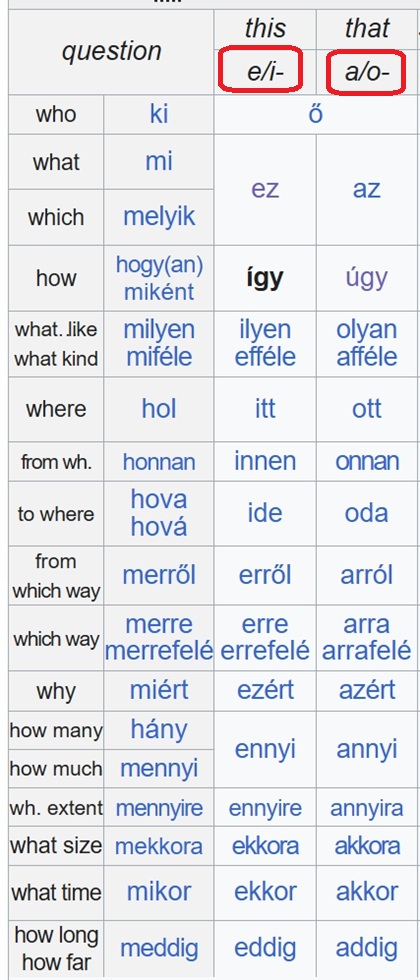

Hungarian seems to like to use high vowels for pronouns that represent things close, and low vowels for pronouns that repesent things far (ez (close) / az (far); itt (close) / ott (far)).

English does this too to a certain extent (here/there, near/far, in/out, this/that).

It's just more noticeable in Hungarian because the pronouns are combined with question words to make lots of pairs, all stemming from "ez/az" and taking the corresponding high vowel/deep vowel.

Oh! and the last small word I wanted to note down for now is "some" which is "néhány." For some reason I always mix it up with "néha" which means "sometimes."

"né-" is something you put infront of adjectives to show it is unspecific.

The "hány" in "néhány" means "how many?"

Which is why "néhány means "some"

The "ha" in "néha" means "if."

Which is why "néha" means "sometimes."

Up to now, we have mentioned suffixes, but we have not mentioned prefixes. Hungarian doesn't really have prefixes (well, actually it does have a prefix: "leg-" which means "most" as in "best, biggest, etc"), instead of prefixes sticking to the front of words it has coverbs which can stick to the front of words. While some people might call them prefixes, they are different enough from what we are used to thinking of in English words as "prefixes" that they really should be honored with the more accurate term of coverb. In Hungarian a coverb is called an "igeköttő" which means "verb binding."

A coverb is attached to the beginning of a verb to change the meaning of the verb. If a noun is created from that verb, the coverb will exist on the noun as well.

beszél: speak

beszélés: talking [noun] [the "-és" suffix turns a verb to a noun.]

megbeszél: discuss, agree on [coverb "meg" ("meg" can mean various things. In this word "meg" just changes the verb's meaning to another related action)]

megbeszélés: discussion

Unlike suffixes, which must have vowel harmony, coverbs never require vowel harmony.

küld [high vowel word]: send

küldés: a sending [noun] [If this had been a deep vowel word, the suffix would have been "-ás" instead of "-és" Suffixes are required to have vowel harmony.]

átküld: send over [coverb "át" ("over") = deep vowel, küld ("send") = high vowel. As you can see, the coverb is not required to have vowel harmony]

átküldés: a sending over [noun]

A verb's coverb often gets separated and moved to another position in the sentence.

This allows whatever is being focused on to take the place of the coverb. In general, anything that is in focus gets placed immediately in front of the verb. Only in neutral thoughts does the coverb remain attached to the front of the verb.

A neutral thought is a thought which doesn't refute or answer a prior thought or draw our attention to any particular part of it.

In a sentence that uses a question word (example: who, what, where, when, why, how) to ask a question, the question word is the focus. A coverb would get out of the way and move behind its verb to allow the question word to move in front of the verb in the focus position.

However in a sentence that uses a verb to ask a question the coverb would not be separated.

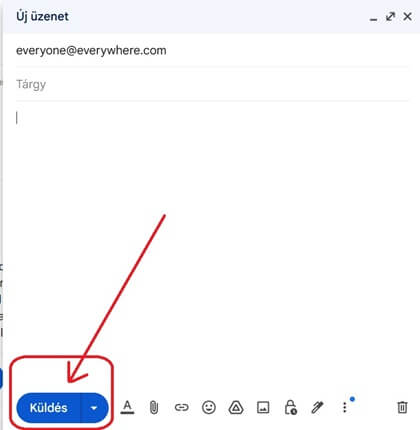

A story containing many examples of questions with coverbs:

Notes before we get to the story:

Quick glossary! (in the order in which the words appear in the story):

To figure out what the rest of the words mean, look at the translation below the story.

Questions:

To make it easier to figure out the answer to the two questions above, in some sentences the focus is circled.

If the word order rules seem too hard to apply, no worries. Right now we are learning concepts theoretically to get an overall view. Later on we will be acquiring the muscle memory so to speak. It will require a level of exposure and engagement that we aren't expected to have at the moment. Eventually we will have enough of a repertoire - for example, through songs, funny responses that we imitate, odd situations that stick in our minds, or what-have-you, and we will acquire a sense of what is natural.

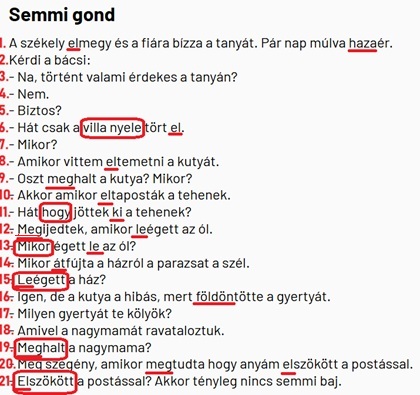

Semmi gond

No worries

1. A szekély elmegy és a fiára bízza a tanyát. Pár nap múlva hazaér.

The Szekély goes away and entrusts the farm to his son. After a few days he returns home.

2. Kérdi a bácsi:

The old man asks:

3. Na, történt valami érdekes a tanyán?

So, anything interesting happened on the farm?

4. Nem

No

5. Biztos?

Are you sure?

6. Hát csak a villa nyele tört el.

Well, only the pitchfork's handle broke off.

7. Mikor?

When?

8. Amikor vittem eltemetni a kutyát.

When I took it to bury the dog.

9. Oszt meghalt a kutya?

So the dog died?

10. Akkor amikor eltaposták a tehenek.

When the cows trampled it.

11. Hát hogy jöttek ki a tehenek?

Well how did the cows come out?

12. Megijedtek, amikor leégett az ól.

They suddenly got frightened when the barn burned down.

13. Mikor égett le az ól?

When did the barn burn down?

14. Mikor átfújta a házról a parazsat a szél.

When the wind blew accross the embers from the house.

15. Leégett a ház?

The house burned down?

16. Igen, de a kutya a hibás, mert földöntötte a gyertyát.

Yes, but the dog was at fault because he toppled over the candle.

17. Milyen gyertyát te kölyök?

What kind of candle, you kid?

18. Amivel a nagymamát ravataloztuk

The one we used to have a funeral for Grandma.

19. Meghalt a nagymama?

Grandma died?

20. Meg szegény, amikor megtudta hogy anyám elszökött a postással.

And the poor thing, when she found out mother ran off with the mailman.

21. Elszökött a postással? Akkor tényleg nincs semmi baj.

She ran off with the mailman? Then there's really nothing wrong.

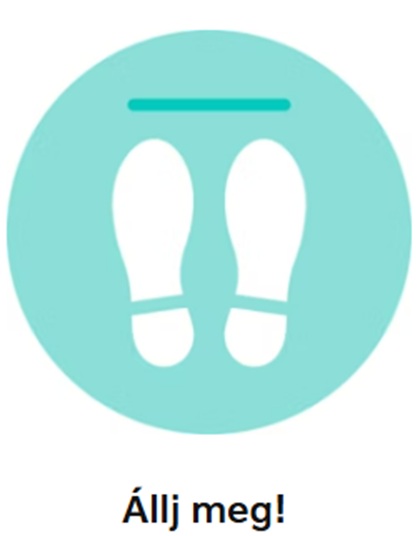

When giving someone a command, the coverb gets separated from its verb as well:

állsz: you stand (not a command)

megállsz: you stop (not a command)

állj meg!: Stop! [command]

And that is a good place to stop. We have come full circle to commands again. There is so much more we're going to do with commands next, but let's digest this all for now.